Telling a more complete story about child welfare

by: Heather Gehlert

original post on Tuesday, April 09, 2019

Gabriel Fernandez. Anthony Avalos. Zymere Perkins. Those are the names that immediately come to mind when I think about how the news media cover the child welfare system. All three were young boys of color and victims of extreme child abuse that resulted in their deaths. The media covered the details of their abuse in haunting detail, leaving images of each one seared in my mind.

The same is true for stories about domestic violence. Although the issue is underreported, when journalists do cover domestic violence, high-profile cases of individual survivors, like Janay Rice or Paula Patton, often dominate headlines. And in today’s digital age, coverage sometimes even includes video footage documenting the abuse.

This trend is not new. Much of our research at Berkeley Media Studies Group shows that when the media report on violence, they tend to focuson specific incidents while overlooking larger patterns and social context. But, when it comes to news about the child welfare system, our team’s latest study reveals that something else is absent from coverage: its connection to domestic violence.

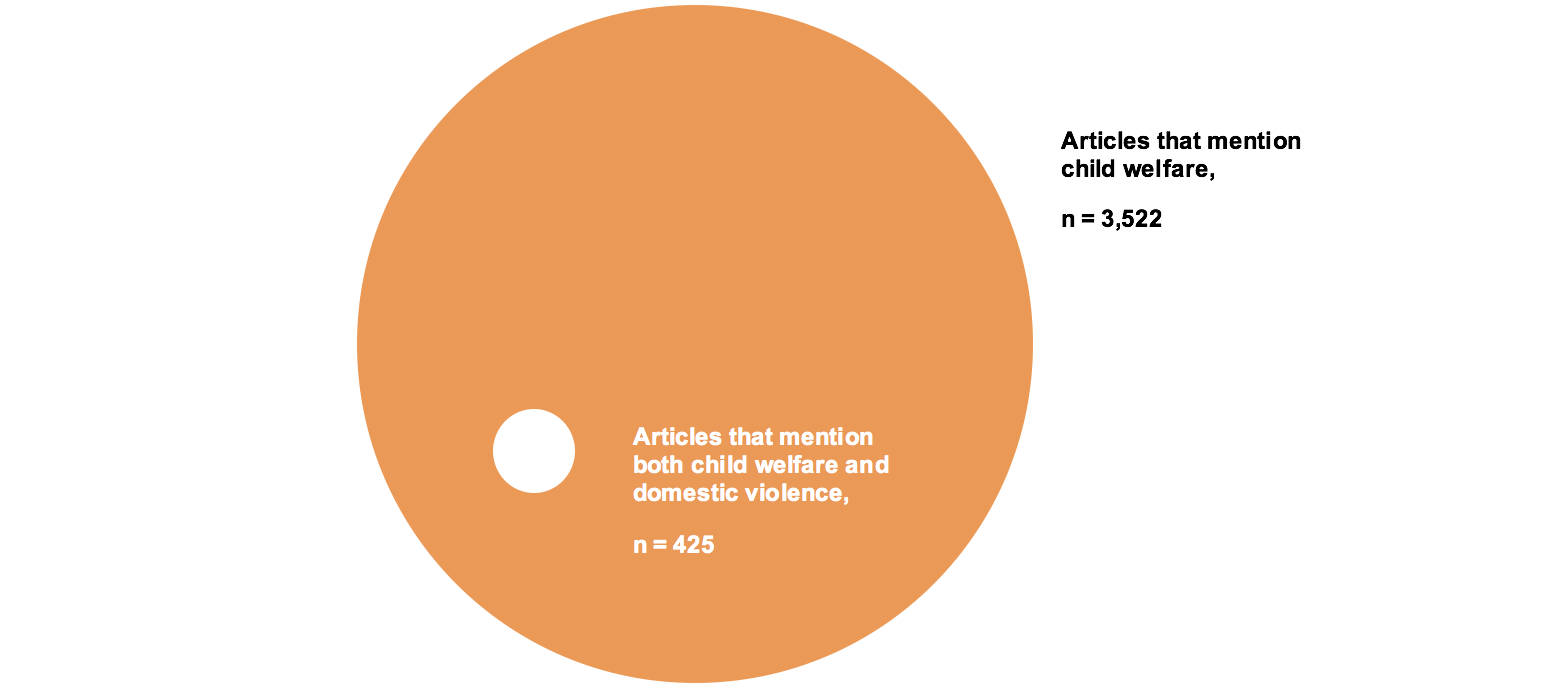

Child abuse occurs in nearly 60 percent of households where domestic violence is identified, but you’re unlikely to learn that from reading the news. In “The Child Welfare System in U.S. News: What’s Missing?“, our researchers found that domestic violence appeared in only 12 percent of stories about the child welfare system, and most of those stories only mentioned domestic violence in passing.

Only 12% of U.S. news from July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2017 about child welfare mentions domestic violence (n=3,522)

“The news shapes how we view issues like family violence, its causes, and what we can do about it,” said BMSG Head of Research Pamela Mejia. “We can’t solve a problem that we don’t know is happening. When important aspects of issues like child abuse and domestic violence are left out of coverage, the people who create policies may be operating with limited information because they often learn about violence the same way the rest of us do — through the media.”

This omission may reflect the reality that child welfare and domestic violence services historically have responded to victims separately. However, in recent years, the Quality Improvement Center on Domestic Violence in Child Welfare has been building on prior efforts in many states to bridge that gap. Reflecting this and other context in news coverage is an important step toward better understanding — and preventing — family violence.

“When news stories highlight programs making a difference in communities through collaborative prevention and service efforts that support the healing and resiliency of families, it’s an opportunity to educate the public about the issue — and to show that change is possible,” said Brian O’Connor, director of public education campaigns and programs at Futures Without Violence, a health and social justice nonprofit aimed at creating violence-free communities.

In addition to obscuring the link between domestic violence and child abuse, BMSG’s study also found that news about the child welfare system often framed the issue from a criminal justice perspective; underlying social inequities were rarely included; and photographs accompanying coverage frequently pictured children of color as victims of abuse, while government officials, child welfare employees, and criminal justice representatives were mostly white.

The good news is that solutions appeared in more than half of news coverage — an unusual finding that breaks from patterns we’ve observed in our news analyses of other forms of violence — and there are ample opportunities for improving coverage.

Based on findings from our report on media coverage of the child welfare system, here are a few steps practitioners can take to strengthen the news about family violence:

Write op-eds and other opinion pieces.

Very few opinion pieces appeared in coverage of child welfare or its connection to domestic violence. This means practitioners have an opening to get their perspectives included through authoring op-eds and letters to the editor or by meeting with editorial boards and suggesting new angles for them.

New to writing opinion pieces? Check out our tips for getting your op-ed published and writing letters to the editor.

Create newsworthy story hooks for reporters.

Practitioners can create news by releasing studies, giving awards, hosting or promoting community events, and finding other creative ways to attract journalists’ attention and expand the frame to focus on the context for family violence. One reason why journalists may report on child abuse and domestic violence from a criminal justice perspective is because they have access to police and court records, which show key dates for events like arraignments and trials. They may be less knowledgeable about the strategies communities are using to prevent violence — or the successes that are already happening. Developing creative news hooks, and telling reporters about them, is one way to connect with journalists and help broaden coverage.

Put data to work.

Numbers can help illustrate the scope of a problem, but numbers don’t speak for themselves. Help reporters — and their readers — make sense of facts and figures by using social math. This technique allows you to restate large numbers in terms of time or place, or by using familiar comparisons to make the data meaningful. Instead of just stating the raw numbers of how many children or families are affected by violence or how many case workers there are in your state, explain how many people are affected every minute or compare the number to the population size of a well-known city.

For example, one campaign designed to educate people about sexual and intimate partner violence noted that the number of people physically abused, raped, or stalked by their partners in a single year was equal to the populations of New York City and Los Angeles combined. Using social math can increase your chances of having your information included — or even quoted — in news coverage.

Become a go-to source for journalists.

Becoming a source for journalists means being prepared ahead of time so that when a reporter calls, you are ready to provide up-to-date facts, concise explanations, concrete examples, and more. One challenge journalists regularly face is finding sources to interview for their stories. Be ready to connect them with sources outside of the criminal justice system, such as advocates and survivors who are willing and able to speak not only to individual incidents but also to the broader context and connections between child abuse and domestic violence. And let journalists know who you are — and that you have this information — well before the next tragic incident occurs. The more available, responsive, and prepared you are, the more likely journalists will be to call you for future stories and hear your ideas for bringing fresh perspectives to the news.

To learn more about our study and how to improve news coverage — including the role that journalists can play — view our full report: “The Child Welfare System in U.S. News: What’s Missing?“